Identity and heritage

Identity in architecture and heritage conservation in Iraq

Ph.D. in Territorial Planning.

The last two decades have been marked by increasing globalization and the domain of a singular identity which is in constant tension with traditional local identities. Keil (1998) reports that “the globalization is seen in the movement of capital, word trade and cultural change, which gains shape above and seemingly outside of national, regional and urban scale and flows into the empty receptacles of local places”. It is commonly agreed that when a city attracts global capital investment, the local places will get through a dramatic change and a global city profile is accomplished, as a result.

Evidence suggests that globalization changes and often destroys the unique features of local places and replaces them with an ‘international architecture’ and a western lifestyle. This usually occurs in cities through urban requalification, neighborhood displacement from old city centers to new neighborhoods, as well as through real-estate speculation and appearance of uncontrolled architectural experiments. The result is a subversion of the identity of cities, and irreparable loss of heritage and historical areas unique fabric and character.

More than ever, architectural heritage everywhere is at risk from a lack of appreciation, experience and care. Some have already lost and more are in danger. As Embaby (2014) states “it is a living heritage and it is essential to understand, define, interpret and manage it well for future generations”.

However, the term heritage itself is ambiguous for many developing countries and often misunderstood. For example, Savino M. (2010, p.158) quoting Gregotti, reports that, “the sudden and impetuous modernization process, together with the acquisition of western technical & typological models, tends to overwhelm all that has not found any shared social definition of heritage, and seems to succumb it to the new forces of change”…. “Similarly, in the Islamic culture countries, where the concept of heritage is not only new and unusual, the term heritage, itself, is seen as something foreign, despite enormous deterioration of such a precious resource such as the medinas of Maghreb, that are “no longer” what they represented for the Islamic society of the past nor “have yet” become anything in the contemporary Islamic society”.

In the post-independence years, many developing countries went through modernization process and shared a common reconstruction experience. In Iraq, like other oil-rich Gulf countries, the modernization approach has extensively adopted. New designs and models are often imported into Iraq from developed countries, or even from a very limited number of regional countries. They reached the country through cyber-routes or digital highways, and land into local territory without encountering any special legal constrains. These offered some benefits and enlightenment but much confusion as well. Many young architects and local designers are attracted to this approach, and often replicate these design initiatives. Practitioners and the political-administrative class are more attracted by perspectives, and often an illusion, that a modernization force can bring, rather than the conservation, appreciation and development of their own architectural culture.

The forgotten experience of Regionalism in Architecture

Regionalism in architecture and “genius loci” has a deep root along the history. Le faivre et al (2001, p.3) notes that ‘Vitruvius was the first to point to the differences in buildings around the world and referred to this phenomenon as “Regional Architecture”, concluding that the arrangement of buildings should be guided by locality and climate’.

Debates over contextualism and identity in architecture have gradually resurfaced since the 1960s, by some prominent scholars. For example, Kevin Lynch (1960, p.8) mentioned that, “the image of the city has three, ‘always appearing together’,-components: Identity, Structure and Meaning”. He describes the identity as “the identification of an object, which implies its distinction from other things, its recognition as a separable entity, in the sense of individuality or oneness”. Following Lynch, several other researchers began to use the concept of spirit of place or ‘genius loci’ allied to the concept of identity of the place. Robert Venturi (1966), for instance, has also started to use the term ‘regionalism’ in architecture as a challenge to conventional trend of modernism, arguing that “buildings are meaningful only in the context of their surroundings”.

In Iraq, the 1960’s and 1970s were considered golden age for the experience of regionalism in architecture and visual art in general. The debate over regionalism and identity has come about since the 1960s through some influential architects, notably Rifat Chadirji and Mohammad Makia. Both made outstanding contributions towards developing regionalism in Iraq and other Arabic countries. They sought after an architecture that is appropriate to the context in which the profession of architecture is practiced.

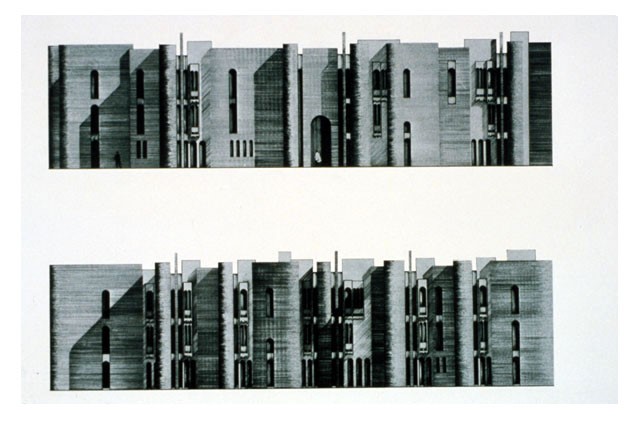

Chadirji’s ministry of Telecommunication building and dozens of other residential and public buildings in Baghdad, as well as his contribution in the rehabilitation master plan of Rasafa, are all examples of an inclination towards creating an identity-linked architecture model, that combines the spirit of Mesopotamia’s art and architecture, (including the Islamic examples), with the rationality of modern architecture (R. Chadirji, 1986).

Almost sharing the same approach, Mohammed Makya (1914-2015), through his genius artworks (including the Raffidain Bank in Kufa, the mosque of Khulafa (1963) and the college of Theology in Baghdad), demonstrates the possibility of combining the spirit of Abbasid-Islamic and traditional style of architecture with modern architecture (K. Makiya, 2001).

During the 1970s, the country has also experienced some innovative pilot projects in the area of identity conservation: for instance, the project for the revitalization of the 5000 years old citadel of Kirkuk, in the early 1970s, by the Dioxides group, as well as the Buchanan project on Erbil citadel, where the concept of ‘environmental area’ has, for the first time, been introduced in the country. Also, in the Resafa Rehabilitation Plan- Baghdad (S. Bianca, 1984), where an ‘adaptive re-use’ approach was used for the first time in 1983 by an international team, operating under the supervision of Stefano Bianca and with the aid of notable architects such as Giorgio Lombardi, Sohiko Yamada, Rifaat Chadirji and Ihsan Fathi. However, these international pilot projects have remained isolated and had little impact on the future development of heritage protection policy as a whole, in Iraq.

Since the end of the 1980s regional architecture in Iraq has had no chance of survival. Twenty five years of the country’s political turmoil, together with a worsening of socio-economic conditions in the 1990s, has played a significant role in an abandoning of the debate over regionalism and identity. As a result, architecture in Iraq has gradually lost the memory of its past. This trend worsened when the country came into contact with the globalized world, after the last Gulf war. All serious formal researches and debates on architecture have ceased to exist, whilst the country has gradually embraced a kind of architecture that is designed in-advance, outside the country, and has little relation with local contexts and identity of local areas and places. Furthermore, there is also a lack of appropriate decision, by both practitioners and urban policy makers, to make architecture more responsive to the need of people and to their place. This is partly because urban planning is conceived as a mere physical practice and decision are still taken by a top-down approach.

The uncertain future of heritage

Despite the integration of Iraq into an international economic system, the country is still suffering from an abnormal technical and legal backwardness, whilst enormous progress is being made, on an international level, in the area of heritage conservation. For example, since the end of the 1960’s a number of international conventions and seminars have been held with the purpose of protecting and improving historical areas, including ‘integrated conservation’ and ‘architectural heritage’; many European countries have adopted a variety of measures to preserve and conserve not only the single historical buildings and monuments, but also the whole areas and setting in which they are located.

Iraq sorely lacks the all new approaches in legislations and norms, which continue to be internationally consolidated and implemented, in the field of heritage conservation.

In order to understand the evolution (but also the confusion) of the heritage protection policy in Iraq, it is worth going a step back in the history. The quest for heritage protection was initiated in Iraq by a British officer, Gertrud Bell, at the end of 1920s, when the country was officially under the British mandate. Following the establishment of Iraqi Museum in 1932, Mrs. Bell promoted a decree in which she made compulsory, the preservation of ancient monuments. This opened a new hope for antiquity protection, but also made injustice to a good portion of the country’s architecture heritage. As G. Cina (2010), rightly notes, “although Mrs. Bell’s decree was innovative for its time, it appeared very restrictive because it extended the right of preservation only to those monuments that were built before the eighteenth century”. In this way, as Azad Hama A. (2013) claims, “scores of historical buildings and monuments, built after 1700, were left outside the sphere of protection and were gradually left to decay with time’[1]. Unfortunately, this attitude continued to exist until the beginning of the 1970s when, finally, the country issued the law of 1974, which gave a wider definition of antiquity and, especially, it extended the right of protection to all historical buildings, including those that have been built after the year 1700. Departments of antiquities have been established in almost every Governorate. This resulted in historic building receiving more and more positive attention. Yet, there still exists a great deal of confusion over the term antiquity and heritage conservation. Old-fashioned methodologies of conservation are still employed by the public authorities and antiquity directorates. As Azad Hama, (2013) notes ‘the protection of single monuments within their historical settings and façadism approach, have quite rightly received much emphasis, but area conservation, or integrated conservation, has not yet penetrated into the heritage directorate or ministerial plan of actions. Research into historical residential areas still remains nominal, let alone the conservation of the entire setting in which monuments are erected.

The recent reconstruction experience in Iraq shows little promise from an identity conservation perspective. Since the installation of a new political system in 2004, the country has dramatically overlooked the issue of identity in architecture and embraced, instead, a modern ‘Gulf countries-style’ type of architecture: traditional architecture with its rich aesthetic and functional elements and complexities, have been seen as merely ‘something of the past’ and being left to decay by lack of maintenance and appreciation. Yet, when it comes to the management of historical buildings, a very selective and sectarian-religious rehabilitation approach, instead, has been carried out. This attitude is reflected now in the existence of sectarian policy by the dominant political groups that are ruling the country. As a result, as Cina’ (2010, p.136) states, “only some historical monuments have received attention: those that have proved most capable of producing consensus or simply more functional to the management of political power”.

Furthermore, due to a general backwardness of local technical procedures and regulation and a lack of a clear policy orientation in the matter of heritage protection, many international and regional architectural firms continue to operate in a discretionary and self-referenced manner.

Yet, the experience of self-referenced rehabilitation projects, made by the outsiders, has proven to lack both social and institutional legitimacy. To give some examples, it is worth reporting the outcomes of two projects designed in 2009 and 2011 by an Italian firm, SGI. The firm has committedly drawn a design for the rehabilitation of historical areas of Mosul and Daquq (Kirkuk Governorate). For instance, in the old Mosul renewal project (2009), in collaboration with Dar-al-Imara studio, SGI has designed a commercial and religious street that crosses the historical area of city center. In this project an adaptive re-use approach has been adopted in place of a traditional single-monument protection approach. The approach was undoubtedly innovative but lacked an institutional consensus, and, therefore, it was never materialized.

In the case of Daquq Renewal Master Plan, instead, SGI has introduced the concept of area-conservation for the conservation of the historical center of Daquq. This part of the project was locally welcomed to some extent. Yet, another area of the project which aroused great discussions and perplexity, on the part of public, was the design of an Italian type of square, almost non-existent in the Islamic urban culture, in the heart of the town. In fact, objections were raised about the demolition that the project would have carried out, in order to make space for the square.

This paper concludes by calling to focus on the theme of identity in architecture and urban conservation within the process of city reconstruction. This is crucial for cities with many centuries of history. This study suggests that the architecture practice in the country should reflect upon local attributes and cognition. Serious formal research about architecture and characteristics of cities, as well as debates over the context and identity in architecture, should be resumed again. Scholars and practitioners need to work towards creating a kind of architecture that is more contextually appropriate and which sensitive to all places and identity issues and which also reflects the cultural, physical and local value system.

Furthermore, the quest for national identity should be extended to all societal sectors: that is, the heritage protection policy should be inclusive and socially shared. Architecture education should include, in its curriculum approaches, a clear understanding of heritage as a vehicle for consolidating and preserving an inclusive national identity. Public participation and awareness, about identity and heritage protection, should be fostered through public seminars, professional writings and media.

Finally, all recent and past international conventions on architectural heritage protection should be well observed. This includes the adoption of ‘area-based’, ‘organic’ and/or ‘integrated conservation’ approach in rehabilitation projects.

Notes

[1] It is not clear why Mrs. Bell set such a time line, but we can assume that, by having an archaeological background and being heavily involved in politics (especially in the founding of Iraq following the collapse of Ottoman empire), she seemed to deliberately overlook the Ottoman architecture legacy in Iraq, which took form between the eighteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century (A. Hama, 2013).

Bibliography

Abel C. 1986, Architecture and Identity: Responses to cultural and Technological change, Architectural press.

Bianca S. 1984, “Designing compatibility between new projects and the local urban tradition”, in Bentley Sevcenko M., Continuity and Change: Design Strategies for Large-scale Urban Development. Cambridge: The Agha Khan program for Islamic Architecture.

Cina’ G. 2010, “Identita’ tra ricostruzione e recupero: il caso dei centri storici in Iraq’’, Archivio di studi urbani e regionali, n.99, pp.134-152, Franco Angeli.

Chadirji R. 1986. Concepts and Influences: Towards a Regionalized International Architecture: 1952-1978, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Embaby M. E. 2014, “Heritage Conservation and Education: An Educational Methodology for Design Studio”, Vol. 10, Issue 3, pages 339-350.

Hama Ahmed A. 2013, The citadel of Kirkuk between the past, present and future, Kurdish Heritage Institute, Sulaimanyah (in Arabic).

Keil R. 1998, “Globalization makes states: perspectives of local governance in the world city”, Review of international Political Economy, 5 4, pp.616-646.

Lefaivre L, Tzonis A. & Stagno B. 2001, Eds., Tropical Architecture: Critical Regionalism in the Age of Globalization, page 3, Wiley-Academy

Lynch K. 1960, The image of the city, p.8, The MIT press.

Makiya K. 2001, Post-Islamic Classicism: A visual Essay on the architecture of Mohamed Makiya, Saqi Books, London.

Svino M. 2010, recensione al libro di Carmen Andriani (a cura di), Il patrimonio dell’abitare, in Archvio di Studi Urbani e Regionali, anno XLI- no. 99. p. 158.

Venturi R. 1966, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, Museum of Modern Art Papers on Architecture, New York.

Images

cover: Tobacco Warehouse, 1974, Baghdad, by R. Chadirji, source: Agha Khan Foundation.

fig.1: School of Theology, 1966, Baghdad, by M. MaKiya, source: courtesy of the author.

fig.2: Raffidain bank, early 1960s, Kufa, by M. Chadirji, source: courtey of the author.

fig.3: The destruction of the thousands years old Kirkuk citadel in 1997, source: Azad Hama Book, op.cit.

fig.4: Gertruld Bell in midle east with Chuchil and Laurence, source: opendemocracy.net.