Between formal and informal: Bairro Prenda

Integrated Master Student, Faculty of Architecture of Oporto University

Part of my master dissertation and based on the paper written for the 5th European Congress on African Studies, 26-29th June 2013, within the panel “Writing the world from another African metropolis: Luanda and the urban question”.

1. URBAN INFORMALITY

The term informal as applied to urbanism has come into vogue in the last decades to describe a phenomenon that has been occurring worldwide. When the formal city does not have the capacity to absorb its new citizens, they find their own informal ways to establish themselves, resulting in the spreading informal settlements. Their name varies from country to country, so as do their characteristics.

In the English language, however, it is important to clarify that slum and informal are not the same, although they sometimes coincide. In 2001 the Millennium Development Goals stated that the definition of slum was related to living conditions. For its part, informal refers to what is not in accordance with certain requirements or rules. In the urban development field, these relate to three factors: land use, construction standards and infrastructure (Jenkins and Andersen, 2011, p. 2).

Therefore, standards draw the line that divides the two realities. But who draws the standards? Much of the legislation of African countries remains from the colonial period. The principles used to define planning legislation originated from the Northern societies and do not always take the environmental, cultural and sociological particularities into account. In addition, the UN try to define worldwide standards, but the results are not contextualized. The particularities shaping the so-called informal city are precisely the values ignored when defining the standards line.

2. LUANDA AND ITS MUSSEQUES

In Luanda, this phenomenon of urban informality was given the name musseques, meaning “red sand” in kimbundo, referring to non-urbanized streets. They were born with the city, developing from downtown backyards, where slaves awaited shipping, to nuclei of huts of the African population and then to dense peri-urban settlements.

Although they were traditionally inhabited by Africans, in the 20th century the increasingly European population also started to establish itself there. This fact distinguishes Luanda from other African capital cities, inasmuch as segregation was not clearly racial, but mostly economic and social.

Also, the distinction between urbanized city and musseques has never been clear. They characterize themselves by their “absence of urban organization, precariousness, overcrowding of miserable population” (Amaral 1968, p. 67).[1] They were traditionally constructed with local materials like wood, adobe and straw (capim). The courtyard was the most important room/space of the dwelling, with high fences that allow privacy for several activities.

Nowadays, however, the walls are usually built of cement blocks and have zinc or fiber cement roofings. The population, too, changed considerably. It is estimated that the majority of Luanda’s inhabitants, around 80%, now live in these informal areas.

3. A CLOSER LOOK AT BAIRRO PRENDA

3.1. Musseque Prenda

It is not easy to define when the area of Prenda was first occupied. Probably it was a rural area in the 19th century. It is, however, certain that there was an arimo (farmland) belonging to a European named Prenda, around which the first nucleus of cubatas (musseque’s house units) formed.

Luanda’s first urban plan (1942) planned a series of curvilinear streets for the area, which were never built, and in 1948 Prenda was referred as a musseque. The plan by the Colonial Urbanization Office (1949) reveals two groups of parallel streets, one of which was actually built and remains until present time.

In 1964, the Musseque Prenda had an estimated population of 13.000 inhabitants. In a comparative study of musseques[2], Prenda was the most populous and the one with more non-African population (Amaral 1968, charts IX, X, fig.13). There was no official commercial establishment in the area, though there were 99 informal (not legalized) establishments, 84 mixed trade shops, 3 bars, 12 groceries.[3] (Idem, p.119)

3.2. Neighborhood Unit no.1

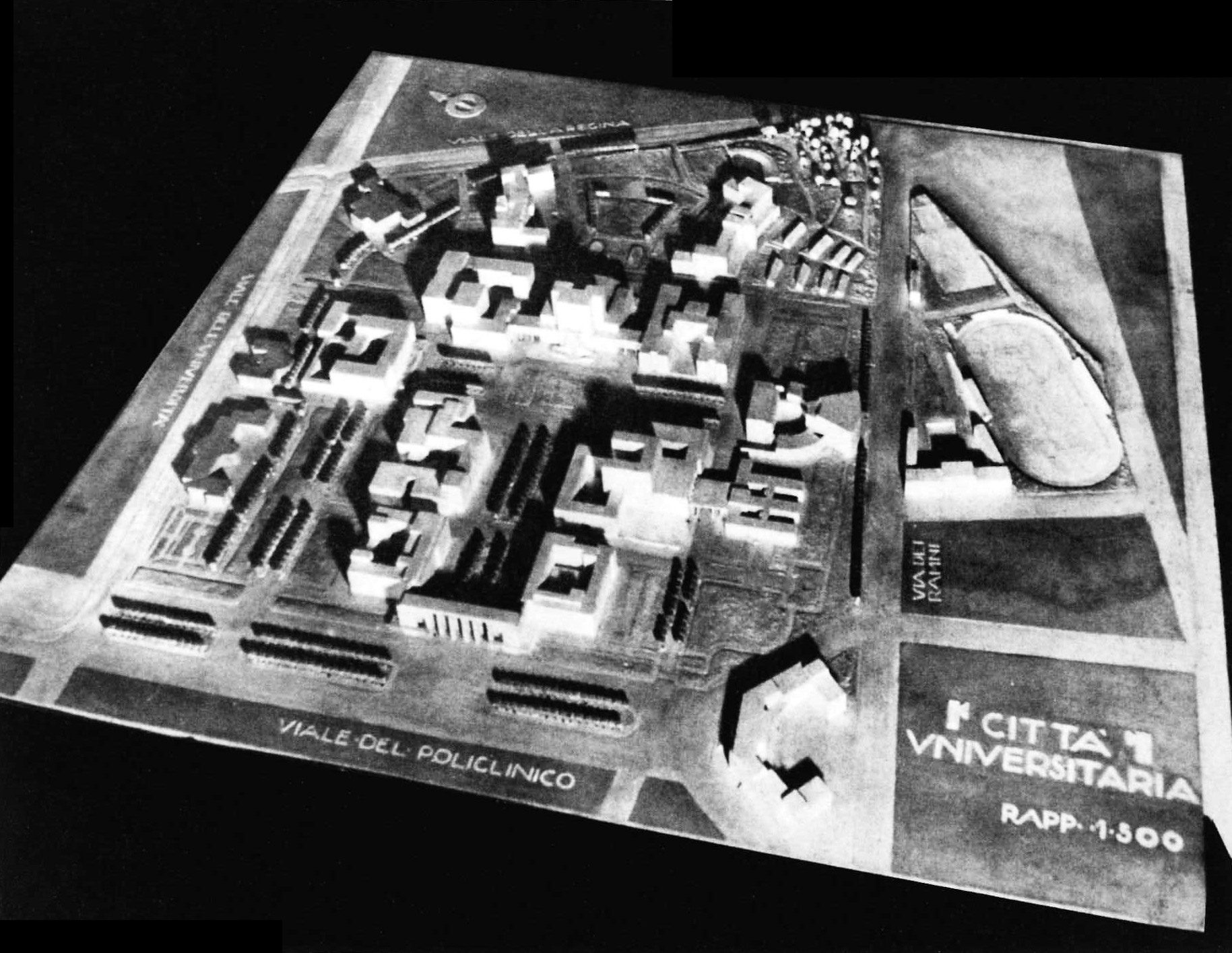

1. Model of Neighborhood Unit no.1 © VIEGAS, S 2012 & The apartment buildings soon after construction © La Modernidad Ignorada 2012

1. Model of Neighborhood Unit no.1 © VIEGAS, S 2012 & The apartment buildings soon after construction © La Modernidad Ignorada 2012

In 1961, Simões de Carvalho and his multidisciplinary team of the Municipal Urbanization Office were put in charge of the new Master Plan of Luanda. Within the logic of linear city, he divides the total urban area into Neighborhood Units, combining dwelling, working and leisure, allowing the city to grow naturally albeit in a controlled manner. Each Unit should have its own facilities within a walkable distance. The 7Vs hierarchy of Le Corbusier is applied to the city’s road system.

Although the Master Plan was never approved or finished, the ideas behind it were applied through Partial Plans for Neighborhood Units as is the case of Prenda, Neighborhood Unit no. 1.

2. Plans of Neighborhood Unit no.1. Housing typologies, facilities and road system (Le Corbusier’s 7Vs hierarchy). © author

The Unit consisted of a combination of four different typologies of housing, depending on the economic capacity. There were detached houses for the richer, townhouses (casas em banda) for the less rich, apartment buildings for the middle class and “houses with a courtyard” for the indigenous, which were to be self-constructed. The idea was to promote miscegenation, with the proposal for it to be inhabited by 2/3 of indigenous and 1/3 Europeans. This was not allowed, but they still succeeded in allotting the opposite proportion.

The location of the buildings is in accordance with the Charter of Athens. The commercial street crosses and organizes the whole unit: along this street were the highest buildings and on both ends sequences of lower buildings. A cinema, a church, a shopping gallery, schools and a health care center were projected in association with this street, but they were never built.

3. First and second plans and cross-section of the high apartment buildings (type A). © author over FONTE, MM 2012

Simões de Carvalho was also awarded to design the apartment buildings, making the project somehow a detail of the plan. Different typologies were combined in each building, from T1 to T4. Most of them were semi-duplexes[4], accessible by an “interior street”, which allowed the air to circulate through the apartment. They were designed with modernist concepts and elements adapted to the tropical climate. The façade design protects the interior from sun exposure with protruded stories and screens (grelhagens). The pilotis in the ground floor also allowed air to circulate and created shaded public space. Twenty of the twenty-nine projected buildings were fully constructed and three were not concluded.

3.3. Informality takes over and continues the formal project

Owing to the beginning of the Civil War, the construction of the neighborhood was never completed. The area of the musseque continued to grow and penetrated the open spaces of the formal plan, in the same way as in the unfinished buildings.

4. Visited townhouse. Main façade and previous courtyard transformed into a wider kitchen. © author, May 2013

4. Visited townhouse. Main façade and previous courtyard transformed into a wider kitchen. © author, May 2013

Concerning housing, most of the detached houses or townhouses are well preserved and seem to maintain the integrity of the original project. Perceptible modifications lie in the search for safety, with bars in the windows and higher walls and fences. In addition, the open space of the courtyard was once important for the extended family to gather during the day, as the scale of the house allows many family relatives to find a temporary home there.

5. Fully constructed apartment buildings. Façade example and the small cages containing generators. © author, May 2013

About the apartment buildings, one must distinguish between fully constructed and unfinished buildings, which remained as skeletons of concrete slabs, columns and stairs. The former exhibit different states of conservation. All over the façade, one can see many satellite dishes, as well as air-conditioning equipments and closed balconies, which disrupt the projected effect of natural ventilation. There is wiring coming out of windows, connecting to generators next to the buildings, or to houses in the vicinity. In the need of space, the pilotis of the ground floors have been occupied, mostly by commercial premises. Whereas the T1 typology does not suit the common large Angolan family needs, the semi-duplex T4, by contrast, offers adequate and proportionate accommodation – and is located near the center, nowadays a most unusual housing offer in Luanda.

6. Unfinished apartment building. © author, May 2013

6. Unfinished apartment building. © author, May 2013

As to the unfinished apartment buildings, newcomers progressively occupied them. In the 90’s, only the lower floors were occupied but now almost all of the building look inhabited. A great variety of materials and openings make up the design of the façade, since walls, windows and all other elements were built in by every single resident. Many wires and pipes connect with the electricity source or with the ground. Even though the unfinished buildings represented an opportunity to obtain a dwelling in a time of need, at present they do not offer desirable living conditions, considering they lack all infrastructures and are unsafe for young children, for instance.

7. Contrast between houses inside self-constructed areas. © author, May 2013

The self-constructed houses form a heterogeneous urban tissue, with a great variety of materials, population and house qualities. The courtyard lost its significance owing to the need for housing and densification took place. Side by side, one can find a two-storey house with permanent materials and a precarious construction with walls of zinc and almost no divisions. The first one invested in infrastructures, like water tanks, generators and pit latrines, the same way dwellers of detached houses or apartment buildings had to do on account of the lack of quality of public supply.

In the second case, people strive to live without any infrastructures, except for “stolen” water and electricity. Although the temporality of the construction is similar to that of the old musseque, living conditions cannot be compared, given, for instance, there is no courtyard to assure privacy in open space and so fulfill family needs.

3.4 Doubts for the future

The future of the neighborhood remains uncertain, as the press reports referring it are not clear. If in 2008 the apartment buildings were to be demolished and the area re-urbanized, in 2009 the buildings were then to be rehabilitated – and gentrification would occur. The project stopped, however, because of problems with the relocations. In 2011 and 2012, the streets that provide access to the formal buildings were paved.

4. CONCLUSIONS

The case of Prenda allows us to see that informal processes have been shaping not only self-constructed areas, but also the so-called formal areas. Over time, the distinction between formal and informal has become ever less clear. The distinction that can be done is between acceptable and insecure living conditions, and both can happen in all typologies.

Informality is often associated with poverty and for that matter being fought. Isn’t it more of a response to poverty and the result of a big effort by Luanda’s inhabitants? The destruction of informal settlements can mean a step back rather than forward. Instead of classifying them as informal, which often leads to their demolition, a more sensitive analysis should be made. When intervening in the city, this informality should be considered as the context and guiding principle.

Luanda is becoming more and more a city of segregation, between gated communities for those who want to find safety and poor resettlement neighborhoods for those without a choice. Should we not learn a lesson from the Neighborhood Units? Although the project for Prenda never reached completion, the result today is an almost self-sufficient bairro, where different housing typologies coexist and there is a sense of neighborliness. Should a city not provide for the miscegenation of cultures and religions, social and economic strata, who all have the same right to public spaces and to share the same facilities?

Bibliography:

- Amarial I. 1968, Luanda (Estudo de Geografia Urbana), Colecção Memórias da Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, no. 53, Lisbon

- Jenkins P. & Andersen J.E. 2011, Developing Cities in between the Formal and Informal, 4th European Conference on African Studies (ECAS 2011), Panel 85: Governing Informal Settlements, on Whose Terms?, p. 2, viewed 22 December 2012, <http://www.nai.uu.se/ecas-4/panels/81-100/panel-85/Jenkins-and-Eskemose-Full-paper.pdf>

- Milheiro A.V. 2010, Luanda in the Future: the Prenda District, Exhibition África/Brasil: A Cidade Popular at Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2010, p.308-317, viewed 29 May 2013, <https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B3MllcndJsdCME5Sbm52QUFLMkk/edit?pli=1>

Images’ references:

- VIEGAS, S 2012, Urbanization in Luanda: geopolitical framework. A socio-territorial analysis, 15th International Planning History Society Conference,p.4 <http://cargocollective.com/arquitecturamodernaluanda/filter/Obras/Bloques-residenciales-de-PrecolFernao-Simoes-de-Carvalho-y-Jose-Pinto>

- Author’s drawing with the model as basis.

- Author’s analysis over FONTE, MM 2012, Urbanismo e Arquitectura em Angola: de Norton de Matos à Revolução, doctoral dissertation, Editora Caleidoscópio & FAUTL , Lisbon, p. 128

- Author (May 2013)

- Author (May 2013)

- Author (May 2013)

- Author (May 2013)

[1] Author’s translation: “ausência de organização urbanística, a precariedade e a insalubridade do povoamento, o amontoamento das populações miseráveis”

[2] Which included Coreia do Norte, Samba Pequena, Prenda, Catambor, Bananeira, Sambizanga, Mota and Lixeira

[3] Author’s translation. Comércio misto, botequins, quitandas.

[4] Also called triplex. They take advantage of a difference of height between floors in opposite façades.